Reprinted with permission from the February 24, 2024 edition of The Legal Intelligencer. © 2024 ALM Global Properties, LLC. All rights reserved. Further duplication without permission is prohibited, contact 877-256-2472 or asset-and-logo-licensing@alm.com.

With the rise of generative artificial intelligence (“GenAI”), many are wondering how it will affect intellectual property law. While much has been written on the subject of copyright law – and the numerous gray areas that will need to be addressed by the U.S. Copyright Office, Congress, and the courts in the next decade – fortunately, the application of GenAI to trademark law is more straight-forward. However, there are still significant risks when using GenAI to create or screen potential trademarks for use.

Let’s start with a quick refresher on GenAI and trademarks. GenAI is a type of artificial intelligence that uses generative models and machine learning from large troves of data to create new content in the form of text, images, and videos. Whereas one might use a search engine like Google to remember the name of a short story about a young couple with very little money trying to buy Christmas gifts for each other (“The Gift of the Magi”), one might use a GenAI chatbot like OpenAI’s ChatGPT to create a new story in the same style as “The Gift of the Magi,” create a sequel to the existing story in modern day times, or create an alternate ending to the existing story. The possibilities are endless, and in a sense, so are the headaches that could be created when considering copyright law. If ChatGPT creates a new story in the style of “The Gift of the Magi” at the instruction of a human being using a specific subset of characters and storylines proposed by the human being, then who owns the copyright in the work that results? For now, the answer is that artificial intelligence cannot be a copyright holder on its own. For any creative work that contains elements created by a human being and elements created by artificial intelligence, the only parts of that work eligible for copyright protection are those created primarily by the human being. At the same time, the law is evolving on this issue daily and could continue to change. This is one example of the copyright concerns that emerge when using GenAI to make new creative works.

Unlike copyrights, which protect expressive works like books, movies, and paintings, trademarks are words, designs, symbols, or some combination of those things used to identify goods or services sold in commerce. For example, “Nike,” “Just Do It,” and the swoosh logo are all registered trademarks of Nike, Inc., in connection with footwear. The Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051, et seq., is the federal statute providing for the system of federal registration of trademarks in order to protect the owner of a trademark from third-party use of similar marks that would create confusion or dilution of the original mark. There are two basic requirements for a trademark to be eligible for protection in the United States: (1) it has to be used in commerce; and (2) it has to be distinctive.

At a high level, a trademark cannot be “distinctive” if it is only generic or descriptive and lacking secondary meaning. If you want to create a brand for a line of running shoes called “Sneakers,” you would not be able to obtain trademark protection in the word “Sneakers” on its own because that is a generic term of the product being sold. If you added a descriptive term to the brand name like “Fast Sneakers,” “Good Sneakers,” or “Classic Sneakers,” you may be able to obtain trademark protection on the Supplemental Register, reserved for descriptive marks (and assuming there are no conflicting marks already registered for related goods/services), but you would not be able to obtain registration on the Principal Register without a showing of secondary meaning. “Secondary meaning” means that a mark has developed a meaning to consumers as a source designator beyond its descriptive, plain, and ordinary meaning, and this can be proven through evidence demonstrating years of advertising and sales that have accomplished the same.

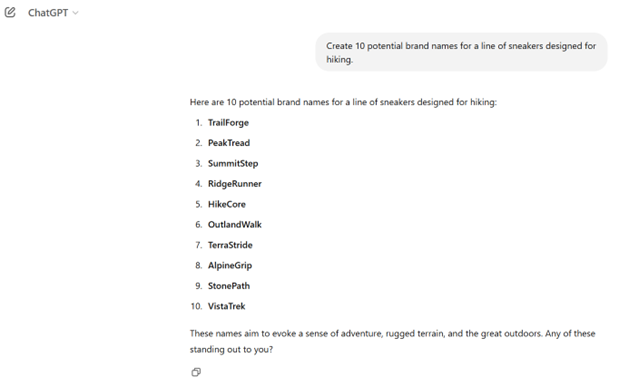

Turning to real world application, marketing departments in U.S. companies are creating new brand names for goods and services every day. Obtaining a federal trademark registration is a valuable component of brand development and protection. It is not difficult to imagine that a GenAI chatbot like ChatGPT would be utilized to help brainstorm potential new brand names for a product. I asked ChatGPT to create a list of 10 potential brand names for a line of sneakers designed for hiking.

This leads to the first question: if ChatGPT comes up with the brand name that a company ultimately selects for its good or service, does ChatGPT own the trademark? The answer is no. A trademark is not eligible for protection until it is used in commerce, and it is the owner of the product or service who holds the trademark rights. Thus, unlike the situation with “The Gift of the Magi” above, there is not a concern that ChatGPT or any other GenAI product would be the owner of the trademark merely because it generated this content. Although it is not impossible to imagine a future where artificial intelligence is running its own business and selling hiking shoes independent of human involvement, for now, this is not a reality, and thus, GenAI cannot be the owner of the trademark merely for generating the product name.

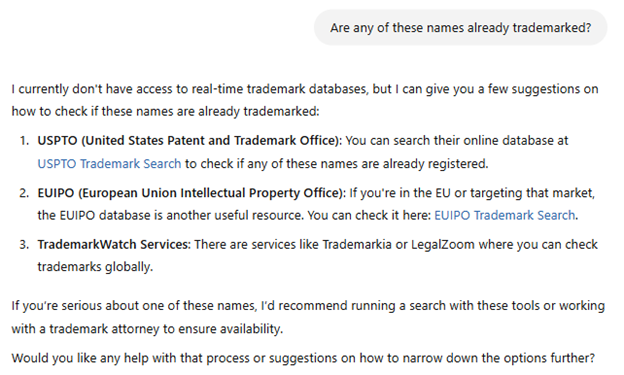

Now for the second question: does this mean these potential brand names are available for trademark protection? The answer is that it depends, but it is imperative that businesses and individuals exercise caution if consulting ChatGPT or any other GenAI for legal advice with respect to trademarks. Looking at the list above, if a company tried to register the mark “RidgeRunner” (suggestion number 4) for a line of hiking shoes, it would almost certainly be refused registration due to the existing federal registration for RIDGE RUNNERS, Reg. No. 7,221,808, owned by Bluefield Baseball Club, Inc., for footwear, clothing, and other related goods. It is also possible that Bluefield Baseball Club would institute a lawsuit for trademark infringement if the “RidgeRunner” mark were adopted and sold in connection with hiking shoes. This consequential pitfall cannot be overlooked when considering GenAI with trademarks. I asked ChatGPT if it could confirm whether any of the above names were trademarked, and the chatbot admits that it does not have that functionality and directs the consumer to a trademark attorney or free online resource.

Even if GenAI integrates a service that searches the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for similar marks, this still does not account for unregistered marks. In the United States, as soon as an individual or company adopts a trademark and uses it in commerce with goods or services, trademark rights attach in what are known as common law rights in a trademark. The United States is a “first-to-use” and not “first-to-register” company with respect to trademark rights. Common law rights can be used to establish priority in a mark over a later attempt to register a similar mark for the same goods and services. If a trademark were adopted that violates another’s prior common law rights in that mark or a similar mark, the same legal risks are presented.

In sum, if someone in a marketing department were to move forward with any of the above brand names presented by ChatGPT without consulting a trademark attorney, he or she would run the risk of committing trademark infringement and potentially being sued for monetary damages and/or spending thousands of dollars to develop a brand that they may ultimately never be able to protect. While GenAI can be consulted as a resource for brand development and it does not carry the same volume of risks for trademark law that it does with copyright law, there are still significant perils if used without the attendant legal advice from an intellectual property lawyer.

Eric R. Clendening is a member of Flaster Greenberg’s Intellectual Property and Litigation Departments. He focuses his practice on trademark, copyright, unfair competition, strategic counseling, and prosecution matters. He has experience litigating many types of commercial disputes in both federal and state courts, including antitrust, contract disputes, employment litigation, and other business tort claims. Eric has secured case dispositive victories for clients in federal and state court at both the trial and appellate level. He also advises clients on protecting and enforcing intellectual property rights online, including the resolution of domain name disputes and matters concerning e-commerce, online speech and conduct, and related intellectual property issues involving trademarks and copyrights.

Eric graduated from Washington University School of Law, cum laude, where he served as associate editor of the Global Studies Law Review. He received his B.A., magna cum laude, from Cornell University. He is licensed to practice law in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, the Western District of Pennsylvania and the District of New Jersey.